Article from The Chronicle of Higher Education.

The City University of New York and the University of Strathclyde, in Scotland, might be located on different continents and separated by an ocean, but a growing number of their faculty members and graduate students are conducting cutting-edge research in tandem.

For the past year, researchers from the Advanced Science Research Center at the Graduate Center of The City University of New York (ASRC) and Strathclyde’s Technology and Innovation Centre (TIC) have been sharing research objectives, state-of-the-art equipment, and interdisciplinary approaches.

It is a unique, expanding partnership between two geographically distant, yet institutionally similar, universities. Both are urban and public. Both traditionally have served under-represented populations. Both have a longstanding commitment to academic research that benefits society. It is not just the similarities that make the partnership effective, however. The institutions’ areas of expertise are different enough that each one provides valuable, new opportunities to the other.

Strathclyde has successfully engineered new technologies with biomedical applications and has built strong relationships with business and industry. CUNY has world-class nanofabrication and bionanotechnology facilities and expertise that can interface these technologies with advanced biological research, and it is seeking to become more entrepreneurial. “Today’s scientific challenges are huge,” says Rein V. Ulijn, director of the Nanoscience Initiative at the ASRC. “You need teams that complement each other because science benefits a great deal from innovation and exchange.”

The underpinning of this partnership dates to 2005, when CUNY launched its “Decade of Science,” a deliberate effort to position itself as a leader in visionary scientific work, to compete more aggressively with other research institutions, and to transfer more of its research to the marketplace. The university set out to recruit top-notch scientists worldwide, and it constructed a building to physically embody the effort’s objectives.

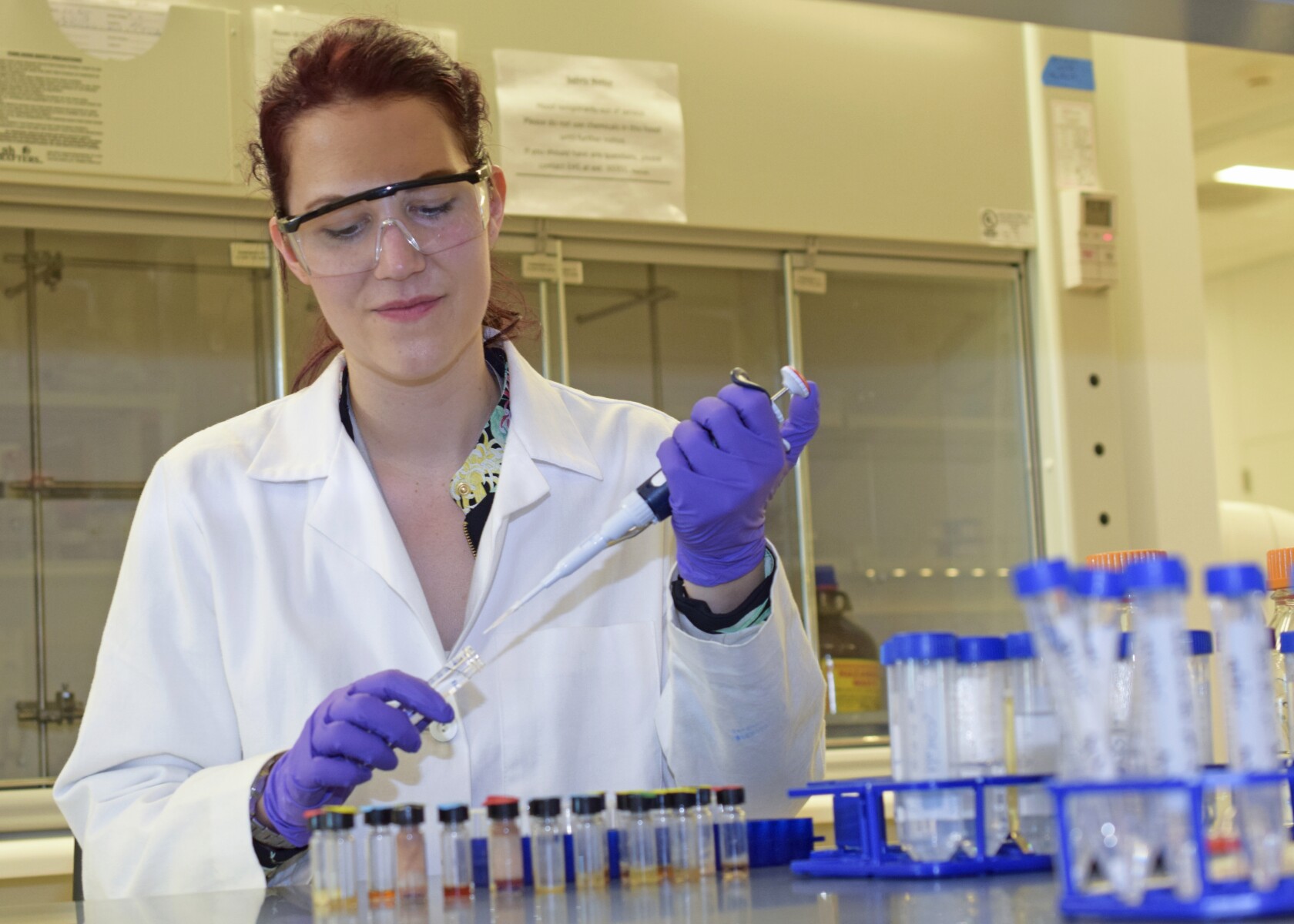

The ASRC structure is an impressive, 200,000-square-foot, glass-encased facility that sits on the south end of The City College of New York campus in Upper Manhattan. Construction started in 2009 and was completed in fall 2014. Each of the five floors is devoted to a different area of global research—nanoscience, photonics, structural biology, neuroscience, and the environmental sciences—and the building’s design fosters collaboration across those disciplines. The facility houses sophisticated, modern instrumentation, including nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometers, and electron and fluorescent microscopes. The ground floor—which also houses nanoscience research labs—includes a 5,000-square-foot Class-100 nanofabrication facility that welcomes researchers from across CUNY, as well as other academic institutions, government and industry. In January 2017, the ASRC became part of the Graduate Center’s university-wide venture that elevates CUNY’s legacy of scientific research and education.

While the ASRC was under construction, CUNY also was actively looking for experts to lead research. In spring 2013, CUNY invited Ulijn, who, at the time, was running a highly regarded nanochemistry lab at Strathclyde, to visit the developing ASRC building. Ulijn’s work is focused on peptide nanotechnology and uses a cross-disciplinary approach to develop materials that could be used in health care, cosmetics, and food science. In 2012, his research led to a spinoff company, Biogelx Ltd., that designs and markets a range of peptide hydrogels that can be used to grow cell cultures.

Ulijn found the opportunities at the ASRC enticing. “I was completely blown away by the scale, the quality of investment, and the energy of the whole place. I left saying I wanted to be a part of this.” In 2014, Ulijn moved to New York to become head of the ASRC’s Nanoscience Initiative and a professor of chemistry at Hunter College, the second oldest of CUNY’s senior colleges.

Ulijn recognized that Strathclyde and CUNY share the same vision. For example, at the same time that CUNY was building the ASRC, Strathclyde was constructing the similarly structured Technology and Innovation Centre, in the heart of its campus. Construction started in spring 2012 and finished in spring 2015. The TIC was designed to incubate new innovations in nanoscience, pharmaceutical manufacturing, photonics and sensors, renewable technologies, and green energy. Researchers at both centers agreed that they could make major breakthroughs and widen their impact if they leveraged their strengths and worked together. Talks began, visits were made, and the partnership was born.

In addition to the advantages of shared research efforts, CUNY benefits from Strathclyde’s expertise in moving research into industry, and Strathclyde gains access to new potential markets and educational partners in New York City.

“The complementary aspects create new lenses through which to view research developments,” says Tell Tuttle

“The complementary aspects create new lenses through which to view research developments,” says Tell Tuttle, senior lecturer in pure and applied chemistry at Strathclyde. “By reframing the research questions, new avenues of scientific exploration can open up and be explored.”

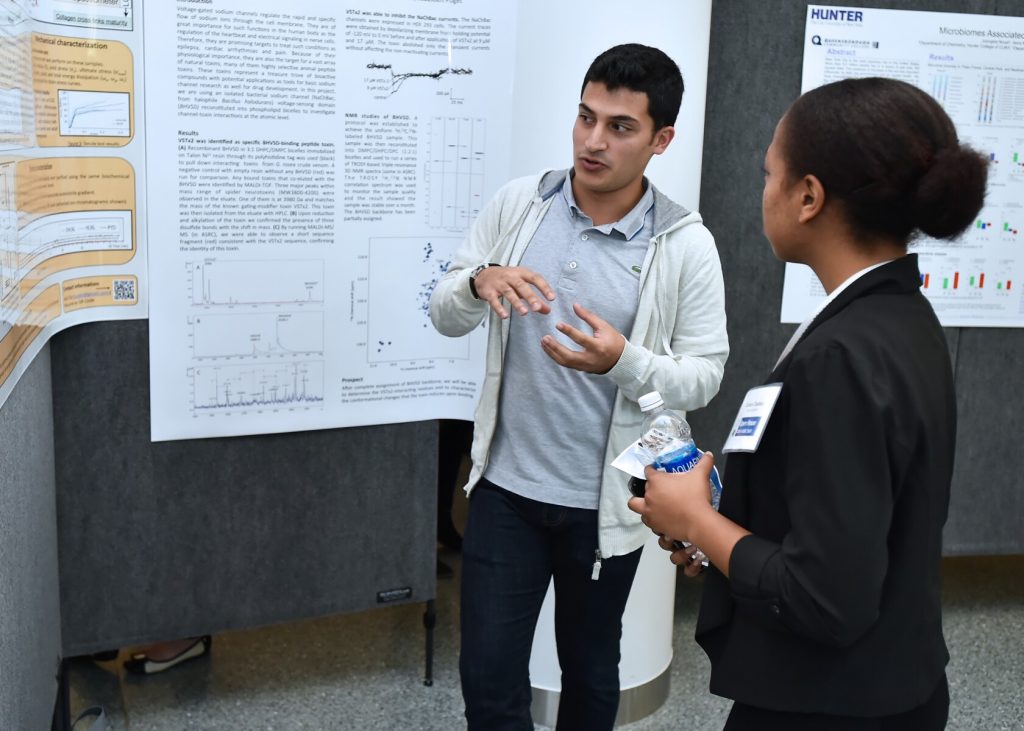

The agreement, signed in March 2016, carries a five-year term, subject to extension, and it sets forth five primary areas of collaboration: nanoscience, bionanotechnology, photonics, structural biology, sustainable cities, and entrepreneurship. So far, the area of nanoscience has experienced the most active collaboration. Five faculty advisors and 10 doctoral candidates from each university, or a total of 30 researchers, have been working together regularly.

Each of the graduate students has a CUNY advisor and a Strathclyde advisor. CUNY advisors Skype and email their Strathclyde counterparts a few times a week. It works similarly for Strathclyde professors with their CUNY advisees. Groups of researchers from both places have met in-person a few times at one institution or the other to discuss their research, and often a CUNY researcher is at Strathclyde, or a Strathclyde researcher at CUNY. Plans are being made to bring everyone together in September. Ulijn says distance hasn’t been a problem, and that, in some ways, it can be a plus. When the researchers do connect, either in person or online, he says, they must be much more prepared, deliberate, and focused because they know time is limited.

The opportunity, she says, to visit a lab in another country and to experience an international perspective makes her a better researcher during the 40 or so hours a week she spends in her lab.

Daniela Kroiss, a Ph.D. student in biochemistry at the Graduate Center and Hunter College, is scheduled to spend six weeks this summer working with Tuttle at Strathclyde to learn how to do computer simulations of the research she has been conducting at the ASRC. She has been building chains and sequences of peptides, and the computer simulations will help her predict new outcomes. Kroiss, who recently completed her first-year Ph.D. examination, says the collaboration adds a whole new dimension to her research. The opportunity, she says, to visit a lab in another country and to experience an international perspective makes her a better researcher during the 40 or so hours a week she spends in her lab. The plan is for her to return from Strathclyde and teach other researchers at CUNY how to do the simulations.

“You can’t just sit in a lab for four years by yourself and turn in a paper,” Kroiss says. “The more you can talk to others, work with different people, and get exposed to different environments, the more motivation and inspiration you get.”

Mark E. Hauber, CUNY’s interim vice provost for research, says the partnership works effectively on an individual level because it is supported at the university level. Any universities considering such a partnership must establish structure and buy-in at the top for it to be successful, he says.

As for the CUNY and Strathclyde partnership, officials feel certain, based on this first year, that the agreement will not only be renewed, but expanded. To date, four of the ASRC’s five initiatives have named founding directors, while a fifth is currently being recruited. Among other endeavors, investigators within the initiatives are mapping the brain’s biochemical circuitry to find cures for brain diseases, exploring ways to use light to diagnose cancer, and analyzing the global water supply. As more faculty members and students join the labs housed at the ASRC, they’ll establish ties with counterparts at Strathclyde. Top Strathclyde and CUNY officials have been in talks about how the institutions can connect the work that each is doing in the area of urban studies to widen the global reach. CUNY’s lead researchers also foresee potential faculty exchanges, and ultimately, perhaps, a joint graduate program. “Research works across borders,” Hauber says. “The collaborative aspects of this partnership are almost limitless.”